By Christopher L. McFarlin, J.D., Faculty Member, Criminal Justice, American Military University

Turn on the news today and stories about police use of force are commonplace. There has been much criticism of law enforcement’s use of force against citizens. While attention to this issue is not a bad thing, a Supreme Court ruling last year is reshaping the way we analyze use of force as it applies to individuals who are held in jail but yet to be convicted, otherwise known as pretrial detainees.

In the past, officers and administrators alike have focused on the subjective justification of actions taken. As such, detention officers are often taught to articulate and defend why they took a certain course of action. However, in 2015, the Kingsley v. Hendrickson case set a new precedent by requiring that alongside law and policy, the objective view of an officer’s actions – without the officer’s subjective interpretation – is enough for proving excessive use of force.

[Related: Stress Management Strategies for Correctional Officers]

Essentially, regardless of how the incident appeared to the officer(s) involved, the only question asked could be how a “reasonable” officer in similar circumstances would have responded. Moving forward, detention officers must be trained to understand that their actions may not be evaluated further than from the objective realm of analysis.

The Kingsley Case

In 2010, Michael Kingsley was arrested on a drug charge and detained in a Wisconsin jail prior to his trial. On May 20th 2010, an officer noticed a piece of paper covering the light above Kingsley’s bed. Officers told Kingsley repeatedly to remove it and each time he refused. Four officers, including Sergeant Stan Hendrickson and Deputy Sheriff Fritz Degner, then attempted to move Kingsley to a receiving cell. When Kingsley refused to back up to the door with his hands behind him for handcuffing, the officers forcibly applied the handcuffs, carried him to a receiving cell, and placed him face down on a bunk.

The parties’ accounts differ about what happened next. The officers testified that Kingsley resisted their efforts to remove his handcuffs. Kingsley testified that he did not. All agree that Sergeant Hendrickson placed his knee in Kingsley’s back. Kingsley testified that Hendrickson and Degner then slammed his head into the concrete bunk, an allegation the officers deny. However, all parties also agree that under Hendrickson’s direction, Degner applied a Taser to Kingsley’s back for approximately five seconds. Kingsley was then left alone in the cell, and officers returned later to remove his handcuffs.

[Related: Correctional Officers Must Master Verbal Judo]

Kingsley filed a lawsuit against officers Hendrickson and Degner for excessive use of force in violation of the 14th Amendment’s due process clause, and the jury ruled in favor of the officers. Kingsley appealed the decision and the case was eventually taken to the Supreme Court. The Supreme Court had to answer whether, to prove an excessive force claim, a pretrial detainee must show that the officers were subjectively aware that their use of force was unreasonable, or only that the officers’ use of that force was objectively unreasonable. It was concluded that the latter was correct.

There are two stages to properly understanding the significance of the Kingsley case. First, most people in the custody of a detention center are pretrial detainees, meaning they have a different legal status than convicted inmates. Second, complaints that an individual’s 14th Amendment rights have been violated are determined by whether the officer’s actions denied the pretrial detainee of his or her due process rights.

Differentiation of Applicable Legal Standards

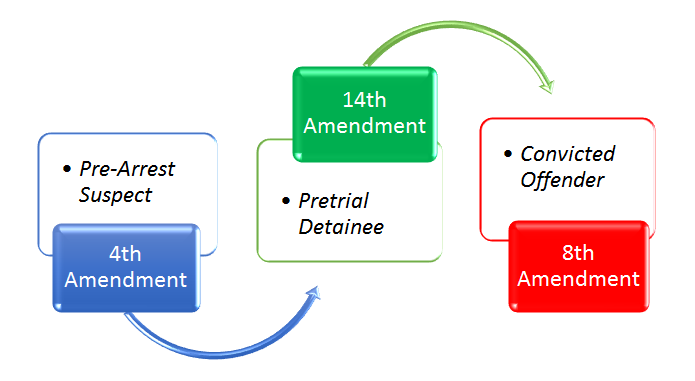

Legal precedents concerning excessive use of force are based on various constitutional amendments. The Eighth Amendment states that cruel and unusual punishments should not be inflicted. Most of the time, when a convicted inmate files an excessive force claim, the basis of that claim is rooted in Eighth Amendment, which is to say the officer used cruel and unusual punishment against them.

Eighth Amendment claims are assessed on whether the actions of an officer constitute punishment. However, constitutional principles only allow a person to be punished once they have been convicted. Since pretrial detainees are still awaiting adjudication of their cases, they must claim excessive use of force under the 14th Amendment’s due process clause.

While it is within the court’s jurisdiction to determine what claims can be asserted on a case by case basis, it will often be based on an individual’s legal status at the time officers allegedly used excessive force. As I teach officers and criminal justice students alike, we should think about the assertion and application of rights in a chronological manner:

A Precedent Applied

Whether a pretrial detainee or a convicted offender, courts will often look at the wanton infliction of pain, or whether the force was used in a malicious or sadistic manner likely to cause harm. To protect their actions against liability, all police officers—regardless of experience—are currently taught to focus on justifications for why they acted a particular way.

However, the Kingsley case is the first indication of a change in how use of force claims will be examined in the future. As they apply to pretrial detainees, an officer’s subjective justifications will no longer hold much weight and if their actions are deemed unreasonable from an objective perspective, the accused officer and employing agency could be held liable.

The objective analysis is assessed on two factors: (1) Consideration of how a reasonable officer on the scene (not the accused) would have responded, including what the officer knew at the time without hindsight. (2) The determination that the officers’ actions were deliberate and related to a legitimate non-punitive governmental purpose. If the officers’ actions appear excessive in relation to that purpose, then there is also potential liability.

Policy & Training Recommendations

Detention officials should immediately begin creating a culture among officers which embodies the essence of this case precedent. The legitimacy and appropriateness of an officer’s use of force from an objective standpoint must be analyzed. Failure to do so could leave an agency open to a host of claims, such as negligence. Negligent actions could include a failure to train, direct, and supervise officers.

[Related: Use of Force Training: A Career-Long Commitment]

Areas that need attention following the Kingsley case include the following:

- Agency policy and procedure manuals

- Supervisor training

- New hire orientation information

- Defensive tactics and de-escalation strategies

- Report writing and articulation techniques

While it can take some time to conduct internal assessments and implement the appropriate course of action, administrators and training officers should take immediate steps to ensure officers understand the new standard. Officers need to know, sooner rather than later, that their justification of their actions is no longer enough for liability protection. Now the way others see an officer’s actions, without that’s officer’s personal input, could determine whether those actions are defensible.

Comments are closed.