By Dr. Chuck Russo, Program Director of Criminal Justice at American Military University and Anthony Galante, Faculty Member, Criminal Justice, AMU

On February 22, a New York City jury awarded $183 million to the families of five of the six firefighters who died or were critically injured in the “Black Sunday” fire. This infamous fire occurred in 2005 when firefighters responded to a burning tenant building to find it had been illegally divided into a maze of apartments. As a result, six firefighters were forced to jump from the fourth floor—two died that day and one died later from his injuries.

The jury found the landlord of the illegally partitioned building is responsible for 20 percent of the damages while the City of New York is responsible for 80 percent (over $140 million) for failing to provide firefighters with personal safety equipment.

The Need for Personal Safety Equipment

The jury found that ropes should have been provided to firefighters, which would have allowed them to safely evacuate the structure, thus minimizing or avoiding the injuries that resulted from jumping.

While this case involves the fire service, the ramifications of this jury award should be considered by all public safety agencies: police, fire and medical services. For example, in an area in central Florida, one major city does not want its police officers to be equipped with or trained on using tourniquets or blood-coagulation agents. The reason? Too much liability.

These agencies need to consider the cost to the city when personnel are injured due to a lack of personal safety equipment. Like in the Black Sunday fire case, not only did the city lose personnel, but it now must make financial reparations that far exceed the cost of providing such equipment in the first place.

Why Police Should Have Tourniquets

There is increasing reason for police officers to be trained in medical response techniques as they are often first responders to mass casualty events. Contemporary active shooter events, such as the Fort Hood shooting; the Boston Marathon bombing; the Aurora, Colorado, massacre and others have made it abundantly clear that law enforcement officers must be prepared to provide immediate life-saving first aid during such events.

This need is especially important as civilian paramedics and fire personnel are traditionally staged away from the scene until it is deemed safe by law enforcement. This extended delay can prove fatal when rapid bleeding or airway obstruction is present and emergency medical personnel are waiting for an all-clear.

Providing Police with Individual First Aid Kits

Before the individual first aid kit (IFAK) is integrated within an agency there must be proper policies and procedures in place. Once drafted, the policy must be approved by all liable entities to ensure all local statutes and training requirements are met. Anytime a new piece of equipment is employed into the field, proper training and recurrent training are an essential part of the plan for successful integration and correct application. Failure to provide officers with the proper and necessary tools to do their job opens up the agency to serious liability.

The Interagency Board of Health, Medical & Responder Safety Subgroup suggests the law enforcement IFAK should include, at a minimum, the following:

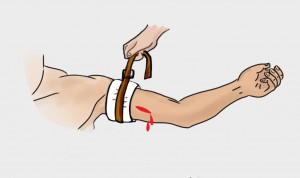

- One commercially available windlass-style tourniquet

- One package of hemostatic gauze

- One roll of compressed cotton gauze

- One mechanical pressure bandage (e.g. ace wrap or other elastic bandage)

- One vented chest seal

- Non-latex gloves

Additional items for consideration include:

- One nasopharyngeal airway

- Small roll duct tape

- A pair of trauma shears

- A zippered bag with compartments or elastic straps holding IFAK contents in place.

The exterior of the bag should have multiple attachment points, allowing it to be mounted in a vehicle, on a backpack or on a duty belt. Several organizations even market ankle-worn IFAK pouches, allowing officers in plainclothes or in uniform to carry this potentially lifesaving equipment.

Restricting access to life-saving tools comes at a cost, as the City of New York has just been reminded.

Will your city, county or state agency find itself in the same position as New York City or does it provide its firefighters, medics and law enforcement officers with the personal safety equipment and medical tools they need?

Had each of the “Black Sunday” firefighters had a $150 hook rescue system and escape rope (as well as the proper training), the outcome could have been very different. To equip each law enforcement officer with an IFAK would cost an agency less than $150 per kit, but could help save a life and could minimize the potential lawsuits an agency may face if officers do not have such personal safety equipment. Spend a little now to save a lot later.

About the Authors:

Comments are closed.