By Gary Deel, Ph.D., JD

Faculty Director, School of Business, American Military University

and Ernest Rahn, Ph.D.

Adjunct Professor of Space Studies, School of STEM, American Military University

This is the second of two articles on how NASA could economically launch more rockets and satellites into space.

In the first part of this series, we discussed how NASA lacks an equatorial launch site and how such an asset could be really important to reducing launch costs for national space agencies and private sector launch providers.

Get started on your Space Studies Degree at American Military University. |

We also discussed how the surface of the rotating Earth moves at different speeds depending on latitude, due to differing distances from the axis of rotation. With that said, the “fastest” place on Earth is actually at the equator (zero degrees latitude), which moves at a blistering speed of roughly 1,037 mph. This speed can make for a significant “helping hand” to launch vehicles.

However, NASA’s southernmost launch site is the Kennedy Space Center in Cape Canaveral, Florida (about 28 degrees north latitude). At that point, the speed of the surface of the Earth is only 894 mph. The difference in rotation speeds between the two sites might not seem like much, but over time the fuel savings could be substantial.

European Space Agency Conducts Most of Its Launches from French Guiana

The European Space Agency (ESA) conducts most of its launches from Kourou, French Guiana, where the latitude is roughly five degrees north. Since this site is so much closer to the equator than anything in the southernmost parts of Europe, ESA member countries save a substantial amount of money on fuel for their launches; the savings is enough to make it worthwhile to ship ESA spacecraft and/or mission components halfway around the world for launch in South America.

New Pact Allows NASA and US Space Contractors to Partner with Brazil on Space Launches

For the same economic reason, the United States signed a “technology safeguards agreement” with Brazil in March of this year. This agreement essentially binds each country to protect any information of the other party that it may become privy to regarding patents, technology secrets and classified data. This agreement was reached with the stated intention that NASA and its private U.S. space contractors could partner with Brazil for space launches.

Why would the United States want to partner with Brazil? Brazil’s space program has floundered in recent years, stemming from several disasters, including a 2003 rocket explosion that claimed the lives of 21 mission support personnel.

It just so happens, however, that Brazil has a launch facility in the town of Alcântara on its eastern coast. Alcântara sits just over two degrees latitude south of the equator. If NASA and its private contractors could arrange permission to use the Alcântara launch site, they could save considerable sums on launch costs.

In a March 2019 Popular Mechanics article, Spaceport Earth author Joe Pappalardo claimed that fuel savings by using the Alcântara site could be as high as 30 percent compared to launches from NASA’s Kennedy Space Center. However, Dr. Ernest Rahn, adjunct professor of Space Studies at American Military University, ran some simple orbital mechanics that suggested the savings would probably be much less.

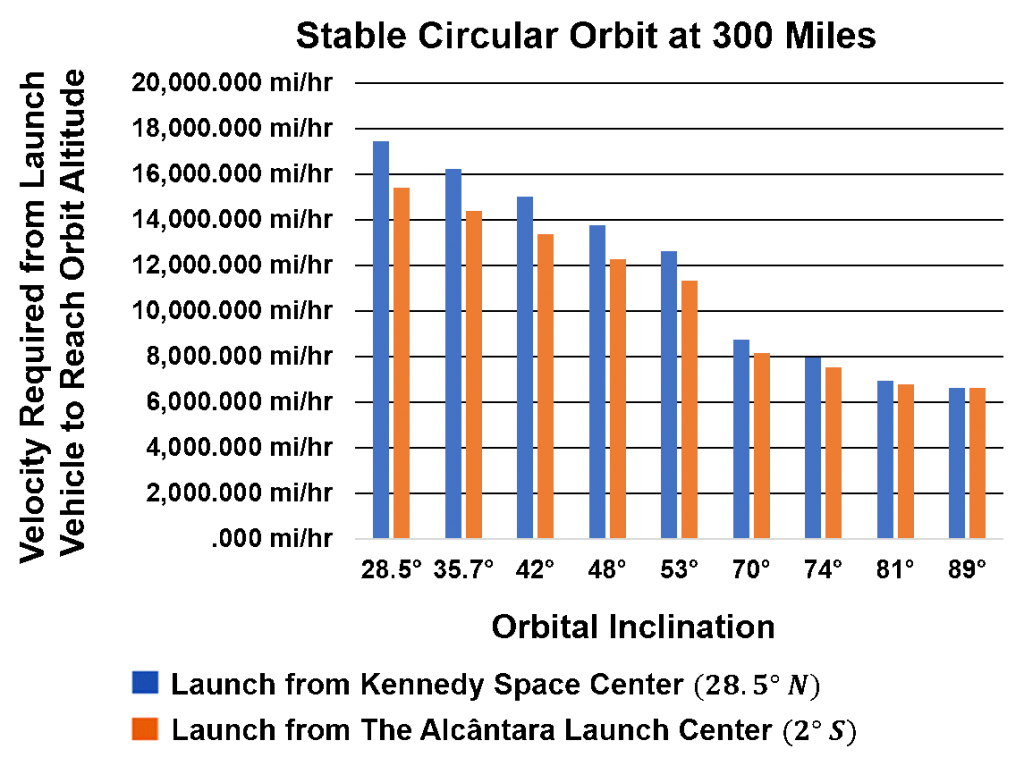

Many factors determine fuel consumption for launches, including vehicle configurations, payloads, target altitudes and orbital inclinations. For the sake of creating a standard measuring stick, the chart reflects launch vehicle velocities needed at the launch sites at Kennedy and Alcântara.

All data are based on orbits with target altitudes of 300 miles and eccentricities of zero (i.e. circular). Different altitudes can obviously require different amounts of fuel, and elliptical orbits can require longer burns along special trajectories. But to simplify our discussion here, we can ignore these additional factors and assume that all of our hypothetical orbits are at the same altitude and perfectly circular.

By holding these factors constant, the chart reveals differences in speeds at each location due to varying surface velocities for a handful of the most commonly used orbital inclinations at or above the Kennedy Space Center’s latitude.

This is important because a site cannot launch spacecraft directly into orbits with inclinations below that of the site itself. So in order to avoid complicated math with secondary orbital insertion maneuvers, we should look only at orbital inclinations that are accessible from both sites.

Notice that the differences in the necessary launch velocity between Alcântara and Kennedy vary considerably by inclination; lower inclinations show greater efficiency gains. This is because Earth’s rotation speed makes less difference as orbital inclinations — the angles at which spacecraft orbit the Earth — become more polar and less equatorial-oriented.

Even a Small Difference in Savings Makes a Different to Launch Costs

All things considered, Dr. Rahn estimates that the average difference in fuel savings between the Kennedy Space Center and Alcântara is probably closer to 5 or 10 percent than it is to 30 percent. However, even 10 percent savings can be considerable.

As an example, for its launch, the Space Shuttle used approximately $1.4 million worth of liquid fuel, so a 10 percent savings would be roughly $140,000 per launch. And that’s before considering differences in the solid rocket booster fuel. Dr. Rahn notes that “it is essentially the equivalent of getting one free launch for every 10 launches.” (The orbiter engines ran on liquid fuel (LOX and LH). The fuel for the solid rocket boosters (or SRBs) attached to the side of the orange tanks of liquid fuel was a solid material that burned to exhaustion to help the orbiter reach target velocity.)

Whether or not the U.S. space agency or its private-sector contractors will actually use Alcantara as a launch site is yet to be determined. Companies such as Lockheed Martin and Boeing have toured the Alcântara launch site. But there have been no official statements about plans to utilize this Brazilian site.

Nonetheless, the interest in using this site is an intriguing development that may eventually give NASA the equatorial launch site access that it has always lacked.

About the Authors

Dr. Gary Deel is a Faculty Director with the School of Business at American Military University. He holds a JD in Law and a Ph.D. in Hospitality/Business Management. He teaches human resources and employment law classes for American Military University, the University of Central Florida, Colorado State University and others.

Dr. Ernest Rahn is a faculty member in the School of Science, Technology, Engineering and Math at American Military University. His academic credentials include a B.S. in Professional Aeronautics and an M.S. in Aeronautical Science – Aerospace Safety Systems and Aerospace Management from Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University; an M.S. in Adult Education from Troy University; and a Ph.D. in Business Administration – Aeronautical Science Management from Northcentral University.

Comments are closed.