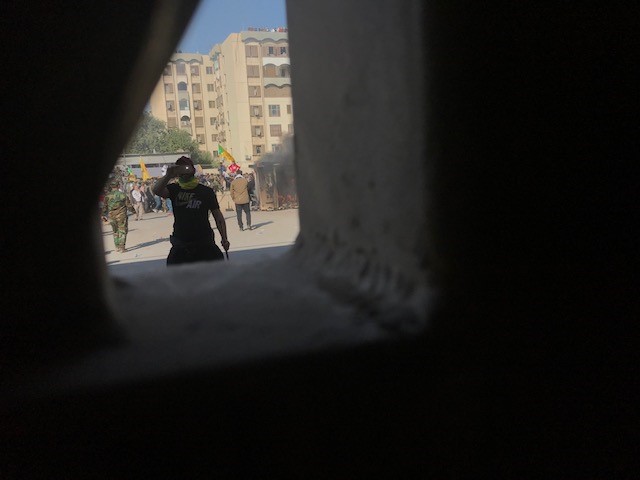

Featured Image: U.S. Marines with 2nd Battalion, 7th Marines, assigned to the Special Purpose Marine Air-Ground Task Force-Crisis Response-Central Command (SPMAGTF-CR-CC) 19.2, conduct security operations at the Baghdad Embassy Compound in Iraq, Feb. 8, 2020. The SPMAGTF-CR-CC is a quick reaction force, prepared to deploy a variety of capabilities across the region. (U.S. Marine Corps photo by Sgt. Kyle C. Talbot)

By Wes O’Donnell Managing Editor of In Military, InCyberDefense and In Space News. Veteran, U.S. Army & U.S. Air Force.

In a recent piece for In Military, I had the opportunity to speak with Assiya Ashraf-Miller, Deputy Assistant Secretary and Assistant Director for International Programs with the Bureau of Diplomatic Security.

During that conversation, I discovered just how important DSS agents’ work is in defending our embassies and other global interests from threats.

The DSS has more than 2,500 special agents, security engineering officers, security technical specialists and diplomatic couriers working and traveling worldwide. Among their duties is the protection of U.S. personnel, facilities, and, in an era of increasing cyber-attacks, information.

Ashraf-Miller also stated that fully one-third of the entire DSS workforce is prior-military. This key fact sparked the realization that the State Department is a great fit for transitioning military who are looking to continue their life of service. But where does one begin?

After reaching out to our contacts at State, we were presented with an amazing opportunity: an interview with several active Diplomatic Security Special (DSS) Agents and Regional Security Officers (RSOs). They were involved in the defense of the U.S. Embassy complex in Baghdad when it came under attack by Iraqi protesters on New Year’s Eve 2019.

Get started on your Homeland Security Degree at American Military University. |

The fact that nobody was killed during that heated event, which elicited memories of Benghazi, speaks to the Americans’ incredible composure under pressure.

My primary objective during the interview was to focus on what transitioning servicemembers can do to best prepare for a career in diplomatic security. After all, veterans possess a willingness to take calculated risks, composure and creativity under extreme pressure and the ability to deal with ambiguity. This makes veterans ideal candidates to continue their service with the State Department after they transition out of the military.

What follows is the transcript of our interview:

Wes O’Donnell: Since our audience is primarily military and veterans, are there any specific leadership traits you can point to that you picked up in the military that frequently assist you in your high-pressure role in diplomatic security?

Special Agent and Senior Regional Security Officer Bryan Bachmann: While the State Department has a leadership development program, the military core leadership principles that one learns in NCO preparatory courses and Officer Candidate School can be translated into leading Special Agents.

The management of stress, conflict, deployment tempo, training schedules – all tax agents and their families much like a soldier, airman, marine or sailor. Learning to lead people from all walks of life in the military helps immensely as DSS Special Agents travel the world and lead local nationals, liaise with host nation police and military forces, and serve alongside people of diverse backgrounds, educations and experiences. The adherence to physical fitness, readiness, and looking out for your fellow agent was founded in large part on military principles.

Special Agent Thomas Kurtzweil: The first thing to understand is that the military does a great job developing leaders; it’s a progressive part of a successful career in the military. No other organization does as great of a job of this developmental process, which includes sending you off to schools, placing you in position of growth, and providing you with quality feedback.

Second, civilian organizations develop managers, and one should know that there is a difference between managing and leading. A leader can do both, but a manager cannot. That is the biggest thing that the military prepares you for when transitioning to the civilian workforce: To maintain composure under pressure, make sound decisions, take care of your people, and manage the chaos around you. Anyone can run a McDonalds during rush hour, but not everyone can run a McDonalds during rush hour calmly, orderly, and take care of their employees.

Special Agent Mike Ross: Teamwork and communication. On December 31, 2019, around mid-morning, a mob of two to three thousand angry individuals crossed the bridge, broke through Iraqi checkpoints, and descended on our compound. They eventually broke through our gates. They burned down three buildings, tried to set our fuel farm on fire, and for hours were throwing Molotov cocktails, rocks, and anything they could find. We needed to rely on each other to make decisions that were going to protect ourselves and the embassy community at large, while simultaneously not escalating tensions by making martyrs of instigators.

All it would have taken was a single gunshot, on either side, to intensify conflict throughout the region. If that were to happen, it would have taken options away from the senior RSO [Special Agent Bachmann], the Ambassador, Secretary of State, and ultimately the President. Collectively, it was our judicious use of force and independent decision making that saved lives that day.

Being a federal agent, many times we work independently on cases or programs. Having a team that is aligned with the larger mission set is important, particularly in an environment like Iraq. It is important to note that many of our colleagues in Iraq were contractors and DOD personnel. The overwhelming majority of them were soldiers and Marines. We had a strong team on the ground and clear communication was crucial in the hours we were attacked and rocketed.

Special Agent Evan Tsurumi: The best training for leadership I got was early opportunities in the military to lead small groups, accomplish tasks, and learn about human psychology through those efforts. I spent most of my service assigned to the Marine Corps as a corpsman and learned their “JJ Did Tie Buckle” acronym, which is accurate (Justice, judgment, dependability, integrity, decisiveness, tact, initiative, endurance, bearing, unselfishness, courage, knowledge, loyalty and enthusiasm) It’s accurate and quite simple to understand.

The most important qualities of a leader are unselfishness, integrity, and respect. If you don’t embody those attributes and are selfish; only seeking to hear yourself speak and abuse your position, your troops will never perform for you because they can’t respect you. If you have no integrity, practice favoritism, cronyism, or only seek to enrich yourself, again, it will show readily. The mission suffers. No one outperforms for someone who they will not respect. Companies spend billions on leadership training; however, you can’t teach unselfishness and integrity.

I also mentally plan and keep planning while never assigning “busy work” to subordinates. I look for others on my team to have the same attributes and, if they do, I trust them. I look two to three steps beyond my immediate problem. Plans fail, but planning is everything. This concept is very difficult and comes with experience to know when to focus on the immediate and then how to evolve that vision into figuring out where you need to be in two, three, four steps or at the 4-hour mark, 8-hour, 12-hour, and 24-hour mark. That is the burden and responsibility of leadership, that, and taking the blame for everything when it goes wrong. You never sell out your subordinates, never ever. Or you are done as a leader, as you should be.

O’Donnell: I have to tell you that, in the realm of federal law enforcement, DS Special Agents may not be as well-known as, say, the FBI or Secret Service. My own personal introduction to DSS was by way of a Tom Clancy novel I read as a young infantryman. What’s a typical day like for a DS Special Agent in Baghdad?

Bachmann: There’s is no easy answer as it depends heavily on your portfolio or section which an agent is assigned to. This can range from protective assignments, investigations, intelligence analysis, Guard Force leadership, military liaison, emergency planning and physical security planning. Regardless, every agent has a 12-plus hour day and is responsible for internal defense roles, mass casualty preparations, and reacting off duty as well. Senior DSS agents will be engaged in managing the 1000-plus contractor personnel, advising Embassy leadership and liaising with Iraqi security commanders.

Kurtzweil: Baghdad for a DSS agent is only a small scope of what a typical agent does overseas. Agents posted at the U.S. Embassy in Baghdad will work in a single security program such as guard force, personal security details, planning exercises, or as a liaison with our partners. Every agent has a role and all are part of the defense of the Embassy. At other embassies, there are fewer agents; it could just be two agents working on everything. The days then are more exciting and you could start your day doing administrative work and then have to go save an American citizen in trouble. But really, the job of a DSS Agent is a “choose your own adventure novel,” – you pick and choose what you want to do with your career, however boring or exciting you want it to be.

Ross: Without getting into specifics, agent responsibilities vary greatly due to the size of the embassy and security programs. Broadly, we are responsible for the protection of the embassy community (from Ambassador down), property, access control, protection of VIPs for meetings outside the wire, physical security, oversight of the local guard force, oversight of emergency response teams, investigations, analysis, and so forth. There are many programs and a great deal of work to be done. Each day brings new challenges and there was no such thing as a typical day.

Tsurumi: It quite depends on your assignment. I was a leader of the Quick Reaction Force (QRF) and would substitute in as the agent in charge of other protective missions, depending on their scale and purpose. I would say the vast majority of what I did on QRF was plan, train, and worry because there is no safety net for the U.S. military in Iraq.

We are “it,” and whatever equipment we bring is all we are going to get. The U.S. Embassy QRF is the only American-staffed tactical response mechanism in Baghdad province, and we are the problem solvers who are activated to provide close combat support and evacuation in kinetic and non-kinetic emergencies. We even support DOD elements within the province. We are five teams with 10 excellent team leaders who managed day–to-day operations and are commanded by DSS agents.

Get started on your Homeland Security Degree at American Military University. |

Most of our mission planning was conducted 24 to 72 hours out, with typical op order, precheck, check, and table top briefings conducted prior to step off. On a mission or reconnaissance, I might be outside the wire from one to 19 hours depending on the distance from base. Depending on how long I’d be out on mission I could have a follow-up mission and there are always emergency call outs. I was very lucky. I also shared my responsibilities with my agent colleagues Doug and Ian on the QRF. Because Doug, Ian and I all shared the same values and work ethic, we accomplished a lot preparing for the worst, and it worked. December 31 and subsequent events were QRF platinum performances.

Training on QRF is a daily occurrence on a litany of problems — vehicle accidents, medical evacuation, combat support, towing operations, TACCOM. During the attacks in December 2019, we added an unusual base defense role. The success we had that day on QRF was due to the indefatigable professionalism of the individual QRF team members and my agent partner, Ian Mackenzie. The two of us probably slept only two to three hours in several days of the attacks and then not much more in the weeks following, commanding all five teams and setting up strategies for defense.

O’Donnell: For transitioning servicemembers who may be looking at a career in diplomatic security, what’s the best degree program you would advise to prepare them?

Bachmann: I strongly advise Criminal Justice and International Relations with a minor in a foreign language. Regardless, one thing that makes DSS such a strong organization is our diverse backgrounds. Some of the best DSS agents that I know are former lawyers, teachers, social workers and private-sector businessmen. All the diverse talents pooled together makes the organization a flexible, dynamic and robust force.

Kurtzweil: Any bachelor’s degree works. DSS is looking for people with experience, those who know how to be part of a team and have people skills. The hardest part most service members have when transitioning is learning how to deal with civilians.

Ross: My undergrad degree was in international relations and it helped me frame the world that DSS agents operate in. Similar to that would be political science. But the degree isn’t as important as competence, decision making, and interpersonal communication skills. I can’t think of a single incident when someone’s degree got them hired or saved the day. In the interview for the position, questions are asked about potential situations you have to find creative solutions to. The degree is not important, but it is a prerequisite for employment.

While we are federal agents, we are also part of the diplomatic arm of the federal government, in the Department of State. Understanding State’s role at large is crucial as we provide law enforcement services to the broader organization and mission. In the military, at least in the Marine Corps, the focus is on readiness and lethality. This is an extremely small part of a DSS agent’s focus.

Overseas we have to understand geopolitical climates, history, sensitive topics, culture, work through complex/multilayered bureaucratic processes, build relationships with host nations, align ourselves with national security strategies, and lead our teams in a suit, not a uniform. I’ve always viewed my degrees as stepping stones, door openers, and checking the boxes. The real impact happens when you do actual work.

Tsurumi: I would encourage them to learn something that will allow them flexibility in their careers. The hiring process for DSS is a competitive and lengthy one. I encourage all transitioning service members to take advantage of the modern educational benefits afforded them. They should seek a college degree in a field which a) sets them apart as an applicant and b) gives them a viable life skill in case they want to change their vocation. For example, a number of transitioning service members like to study criminal justice and homeland security.

Those majors are popular at many accredited U.S. universities; however, to compete for a federal law enforcement job (including DSS) the graduate competes with people who speak two or three foreign languages, have advanced technical and science backgrounds, accounting or finance experience, or extensive international employment. I always recommend students to study science, economics, or accounting to make them more competitive. If the student can learn a foreign language or get a degree in international relations, they stand apart from other applicants.

Classes in business management are useful; running a business teaches many of the logistical skills attractive to the recruiters of Diplomatic Security. If the applicant decides that Diplomatic Security is not for them or the hiring process takes too long, it gives them other options. Additionally, enforcing federal law demands a knowledge of finance, economics, information technology and accounting. Criminals commit crimes for benefit and the type of crime we investigate is complicated. Between ourselves and the FBI, HSI [Homeland Security Investigations] and DEA, I think all agency recruiters look for applicants who can understand data and analyze it effectively. I can speak with authority as a Diplomatic Security Agent as well and as a former HSI Special Agent/Program manager.

O’Donnell: I was surprised to learn that the Marine Security Guard (MSG) reports to the RSO, not their traditional chain of command within the Department of the Navy. How do the Marines fit into your mission?

Bachmann: MSGs are unique in that they are jointly trained by the Department of State and the Marine Corps. Operationally, their chain of command at an embassy is through the RSO. The MSGs are a separate entity from the Defense Attaché Office or other military organizations found at a post. Marines are responsible for the protection of classified information, internal defense of the compound, and stand as a reactionary force to aid the RSO in contingencies on an embassy compound — a fire, intruder, natural disaster, or attack).

Kurtzweil: MSGs are an integral part of the Regional Security Office team. The Department of State has a memorandum of agreement that outlines the roles, relationships, and responsibilities between the two. At embassies worldwide, the DSS’ mission is the MSG’s mission: to protect people and information at the embassy. We train and take care of the Marines, trying to make their stay as enjoyable as possible. Some MSGs later become DSS agents.

Ross: Marines have been charged with protecting U.S. embassies since the late 1940s, but the relationship between Marines and State started earlier when Marines would go on special missions to protect Americans in austere environments. Marines are unique in that we are expeditious in nature and can provide immediate responses to emergencies so it was a natural fit. It started with the Foreign Service Act of 1946, when the Navy authorized the Marines to fall under the operational control of the chiefs of diplomatic posts.

It wasn’t until 1949, however, where the first Marines would be sent to serve in Morocco and Thailand. An interesting fact, Morocco was one of the first nations to recognize U.S. independence. Currently, MSGs fall under the operational chain of command of the Regional Security Officer (RSO) at their respective posts. The RSO, a DSS special agent, is responsible for the safety of personnel and property at our missions abroad, and the MSGs fall under them. I was fortunate in my Marine Corps career to have been an MSG. Outside of higher education, being [a MSG] opened many doors.

MSG duty exposes Marines to a very different culture and government service. Marines are known to be tough and DoS is known to be intelligent. Being strong and smart is a dangerous combo and that is what many of my MSG and DSS colleagues strive for.

Get started on your Homeland Security Degree at American Military University. |

Tsurumi: The MSGs fall under the operational control of the Regional Security Officer at Post and are administered in conjunction with the Marine Corps through their parent battalion. The vast majority of U.S. diplomatic missions around the world have few security-cleared Americans in security roles and thus, the Marines are force multipliers for the RSO. The Marines provide the backbone of the innermost security layer at post, responsible for lives and critical information systems under the direction of the RSO.

O’Donnell: This is just to satisfy my own curiosity: Have you noticed any friendly inter-agency rivalry, like there is between branches in the military?

Bachmann: We always have a friendly rivalry with other agencies such as the FBI, DEA, NCIS, and so forth. But at the end of the day, everyone is conscious that, while we all have our own investigative specialties, the security of Chief of Mission personnel lies squarely on the RSO and DSS team.

Kurtzweil: Of course, there is always friendly inter-agency rivalry; we wouldn’t be professional organizations without it.

Ross: We are so unique and small that I don’t know if many people are aware of us. An agency we work with routinely is the Secret Service. It is my experience that DSS is a more sought-after career than the Secret Service. From the day we graduate from our basic course, we have more autonomy and responsibility than basic Secret Service agents. I don’t know about rivalry, but I do know that I am fortunate to be DSS. To give you a sense, imagine being directly on the frontline of U.S. elections and campaign events. Politics has become extremely divisive over the last decade. I’ve worked with some amazing Secret Service agents, but they get burned out fast and the job can take a heavy toll on families.

O’Donnell: For veterans, the adjustment from active duty can be really difficult. Veterans sometimes struggle to find the sense of community that they had. They also struggle to find the structure and the pace of operations they were used to; even in peacetime – the operational tempo in the military is very high. What was that transition like for you personally?

Bachmann: I have been on the job for 23 years now, and looking back at the early days the travel, last-minute deployments, long training cycles is very much akin to the military service. It was challenging, but the military provided a great foundation for success. I found in DSS the same comradery, sense of mission, and support network. In between the military and Department of State service, it was a little unnerving to be separated from a unit, team or organization. I am very grateful to have found an organization with a similar work ethic, values and purpose as the military.

Kurtzweil: I know this feeling. I left the infantry for a staff officer job at the Defense Intelligence Agency. I was climbing the walls after one month. DSS has provided relief from that, but there will never be anything like the military with the camaraderie and high op tempo. DSS lets me pick and choose my work; however, busy or slow I want my work and, for the most part, who I want to work with.

Ross: After active duty, I transitioned to the Reserves and have bounced on and off active orders. I currently have six DD-214s because the job market in the mid-2000s was dismal. I always recommend to active duty colleagues to look at Reserve opportunities because there will be a time where you miss aspects of being in [the military]. As I write this, I have less than two years until I can retire as a reservist and have been promoted the same time as my active duty contemporaries.

I came off MSG duty to Metro-Detroit in 2006 and the only job I could find was being a barback in a hip-hop club downtown. It hurt the ego to clean up vomit and spilled drinks after amateur rap concerts. It is important for veterans to understand that losing a sense of community is normal. I attribute my success after active duty to being willing to capitalize on opportunities and that meant humbling myself and moving. In the end, transitioning isn’t just off active duty. It may be a decade long process in finding out who you want to be and what you want your life to look like.

If you only talk about your glory days in the military, you should have stayed in or at least gone into the reserves. If you decide to leave it behind, utilize what you learned in the military to pursue your personal and professional goals. This may mean taking many jobs until you find the one you truly like. Resiliency is the key. There is also an incredible amount of resources for vets to start a small business. Get after it! If you took the same intensity and discipline you had in the military and applied that to your civilian life, you will be wildly successful.

Tsurumi: Again, I think the answer depends on your military experience, emotional maturity, and MOS. Some MOS are a lot easier to transition to civilian life and require significant exposure to the civilian world. What kind of support network service members have outside the military and how prepared they are to leave the military also plays a role. Those who succeed are those who have concrete plans, contingency plans, and have taken advantage of the educational benefits afforded to them. They are also those who are emotionally mature to leave the service and have managed their expectations. I met many who couldn’t wait to get out; did not have a plan, but hated and blamed everything on the military. Those individuals tended to have problems adjusting.

O’Donnell: Final question – What’s your best piece of advice for that transitioning servicemember who is separating within a year and wants to continue his or her federal service?

Bachmann: My advice is to apply early and often. If you get turned down by one organization or position, keep plugging away and sharpening your resume, interviewing skills and written exams. Look at early interviews as “training opportunities” for future opportunities. It is important to network, learn from others and focus as if it were a “mission.”

Kurtzweil: The world is an ocean, pick where you want to swim. If it’s joining the federal workforce, do not forget to buy back your military time for federal retirement. Above all, have fun and enjoy yourself.

Ross: I would suggest getting what you can take first and be realistic. I’ve seen many friends/vets have a chip on their shoulder and think they deserve great, high paying jobs when they get out. You may have to start at the bottom again and that is okay. Time goes by fast. Once you are in the [federal] system, which can be difficult to get in, you can continue your federal service, which means marching towards a federal pension. From there, work hard and build up relationships, a network.

Then, continue to build up your resume and keep an eye on higher-level positions. Find healthy hobbies, learn about investments, don’t go into debt, stay fit, and don’t forget that you served this nation. That means serving people you may agree or disagree with ideologically. No one owes you anything. If this is difficult for you, seek your local VFW or American Legion. I’m a member of both and have made lifelong friendships with those brothers and sisters. There are also many newer veteran organizations that do service projects and incorporate physical fitness.

Remember, Arlington National Cemetery and cemeteries around the world are filled with young men and women who would trade places with you if they could. I am confident they would want you to be happy, healthy, and successful. Don’t let the negativity get you down. Take the good lessons with you and dump the bad. If you really want to enrichen your post-military life, seek volunteer opportunities to help those who can’t help themselves. Starting at a nursing home or a Veterans Affairs assisted living facility is a good start You will gain perspective and you will light up their day. This would continue your legacy of selfless service and honor. Trust me, we need more people like that in the world. Lastly, remember heroes and the men and women who served before you. Remember living Medal of Honor recipients like Kyle Carpenter, Florent Groberg, Dakota Meyer, William Swenson, and Sal Giunta from the global war on terror. Remember legends like John Basilone, Audie Murphy, Daniel Inouye, and Roy Benavidez in wars before.

This is your veteran family. These are real heroes. Now go forth, work hard, thrive…and don’t forget to PT! “Greater love has no one than this, that he lay down his life for his friends.” – John 15:13. I made many mistakes along the way. If you want to reach out to me to ask any questions, I will give it to you straight, no chaser. m.ross@veteran.me. Semper Fi.

Tsurumi: Don’t assume that the transition or hiring will be seamless and quick; the federal government hiring processes for most Special Agent jobs (not to mention other fields) is dependent on congressional funding and is affected by government shutdowns and many other unforeseen complications. Never assume that you are owed anything and that it will be easy.

It’s also still much slower than the hiring process in the private sector, especially for agencies that require a security clearance. Make sure you have all your copies: DD-214, medical records, certifications you obtained while in the service. If you don’t have copies, assume it never happened. The adage “two is one and one is none” applies here. Create a USAJOBS account and keep it updated throughout your military service as opposed to trying to create one the night you realize a job you want opened up. Just as you entered a different culture upon enlistment/commissioning, you are entering a different phase of life now and you have to adapt; the work and world are not going to adapt to you.

Fortunately, now we have a society in which veterans’ rights and the welfare of veterans is extremely important to Americans. That is a privilege and if you read American history, that was not always the case. Take advantage of that privilege and the benefits, which those before you fought for.

You have a lot of tools: significant VA benefits to include educational and vocational training allowances, opportunities to join the Reserves or National Guard, and transition programs through major companies. Begin the planning process about exiting the military ahead of your last year and do your research about what kind of life you want to lead and where you want to lead it to.

More information for veterans about careers at the U.S. Department of State

The appearance of U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) visual information does not imply or constitute DoD endorsement.

Comments are closed.