By Wes O’Donnell

Managing Editor of In Military, InCyberDefense and In Space News.

The tragic disappearance and murder of Army Specialist Vanessa Guillen, stationed at Fort Hood, Texas, has cast new light on a decades-old problem in the world’s finest military: sexual assault and sexual harassment.

The death of Spc. Vanessa Guillén at Fort Hood has brought renewed attention to the long fight against military sexual violence. The family have maintained that Guillén was sexually harassed by superiors at Fort Hood, however, Army officials have said there is still no evidence linking sexual harassment to Guillén’s disappearance.

Despite this, women veterans are making their voice heard. In 2018, members of the Service Women’s Action Network, or SWAN traveled to Washington for the #MeTooMilitary Stand Down protest outside the Pentagon.

Get started on your Homeland Security Degree at American Military University. |

On October 15, 2017, the original #MeToo hashtag went viral when actress Alyssa Milano posted on Twitter, “If all the women who have been sexually harassed or assaulted wrote ‘Me too’ as a status, we might give people a sense of the magnitude of the problem.”

By the end of the day, the simple two-word phrase had been used more than 200,000 times. It was tweeted more than 500,000 times by the next day. On Facebook, the hashtag #MeToo was used by more than 4.7 million people in 12 million posts during the first 24 hours.

High profile support from celebrities like Gwyneth Paltrow and Jennifer Lawrence, among many others, pushed the conversation about widespread sexual abuse into the national spotlight. But the phrase had been around since 2006, coined by sexual harassment survivor and activist Tarana Burke.

The 2017 viral #MeToo hashtag resulted in a tsunami of changes including increased awareness and empathy, new policies and laws, media coverage, and a national conversation about sexual harassment and sexual assault beyond Hollywood, reaching industries like academia, corporate America and government.

#MeToo and the US Military

Contrary to the popular notion that the military is a socially conservative organization, the Department of Defense (DoD) is actually one of the more progressive institutions in the United States, especially when dealing with equality.

President Harry Truman’s 1948 Executive Order (9980), which created a Fair Employment Board to “eliminate racial discrimination in federal employment” would set the stage for the desegregation of the military, six years before the Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court decision ordered the desegregation of American schools.

And yet, sexual assault and harassment in the military have plagued the services for decades, despite many commanders’ best efforts to get it under control.

Serving in the U.S. Army infantry, at a time when combat arms jobs were still men only, I never once received any Military Sexual Violence (MSV) training. However, serving in the Air Force alongside women, at least once a year we all were given the mandatory one-hour PowerPoint presentation on why rape is bad.

The truth is that on issues of MSV the military is woefully behind the society it protects.

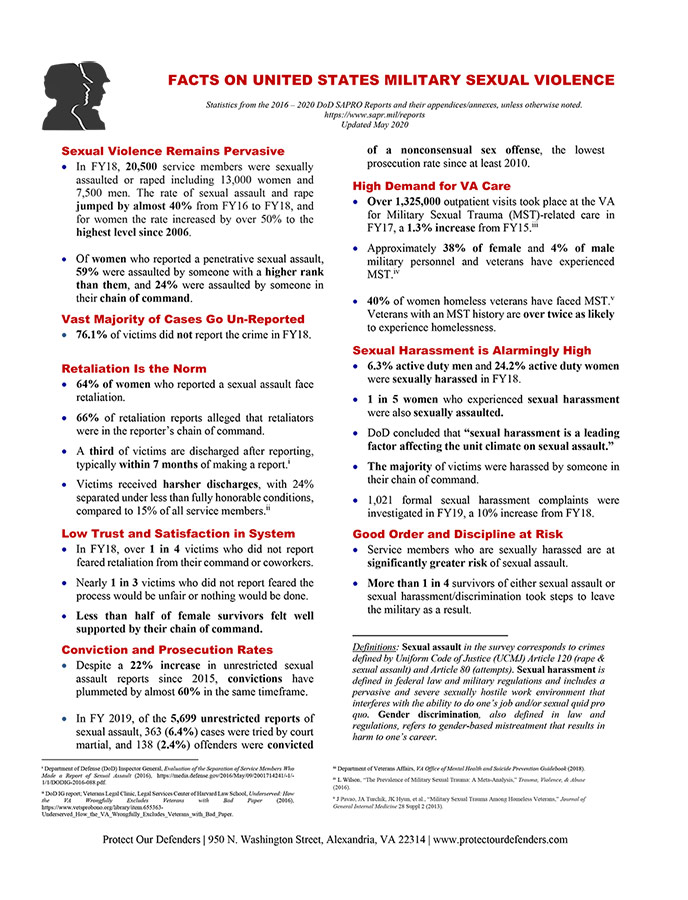

In FY18, 20,500 service members were sexually assaulted or raped including 13,000 women and 7,500 men. The rate of sexual assault and rape jumped by almost 40% from FY16 to FY18, and for women, the rate increased by over 50% to the highest level since 2006.

Of the women who reported a penetrative sexual assault, 59% were assaulted by someone with a higher rank than they had, and 24% were assaulted by someone in their chain of command. What is worse, the vast majority of MSV cases go unreported. A staggering 76.1% of victims did not report the crime in FY18!

Fact Sheet used with the permission of Protect Our Defenders.

In this era of incredible progress in the areas of racial equality and justice and a reckoning of civilian sexual abuse, the U.S. military is not going to solve the problem of MSV with a one-hour training session for its frontline troops.

In fact, the problem appears to stem from the DoD’s reactive nature to reform.

In 2017, the Marine Corps was rocked by scandal when investigative reports revealed that photos of naked servicewomen were shared on a closed Facebook group called “Marines United.” After the story sent shockwaves through the ranks, the military initiated a number of reforms, including a bill banning “revenge porn.”

It was only after the scandal made the news that the Corps performed an investigation that resulted in the court-martial of seven Marines.

But the Marine Corps is certainly not alone. In April of 2019, a female servicemember found a camera in a women’s bathroom on the Navy warship USS Arlington.

In addition, for 10 months on the USS Wyoming, an Ohio-class ballistic-missile submarine, a group of sailors filmed at least a dozen women serving aboard the Navy sub as they undressed and showered. The videos were then distributed among other sailors.

Why Is the Military Struggling to Get a Handle on Military Sexual Violence?

The first problem is that 62% of victims who reported sexual assault in the military faced professional and social retaliation. This creates a disincentive for victims to come forward which contributes to the astronomically high percentage of victims (76.1% in FY18) who simply chose to not report the crime.

One in three victims believed that reporting sexual harassment would hurt their career, that the investigation would be unfair, or that nothing would be done. The reason why these victims believe this is nearly half of victims were encouraged to “drop the issue” by their chain of command or coworkers and 41% said that the person they reported the crime to took no action.

In addition, the bureaucracy in the military, the nation’s largest employer, makes it difficult to achieve meaningful change in a reasonable amount of time. Couple this with the male-dominated culture and worries that holding people accountable for sexual assault and harassment might destroy unit cohesion, and it appears that military sexual violence could only get worse.

Some in government, like Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand (D-N.Y.) have advocated for removing unit commanders from the reporting process. However, the Judge Advocates General notes that the Gillibrand plan would create a system that is “disconnected from the chain of command, unit discipline, and operational mission” and would “damage the integrity of the military justice system and critically diminish the essential premise of command authority.”

Writing for The Heritage Foundation, Charles “Cully” Stimson says: “They, [unit commanders] and they alone, must retain the ability to refer suspected criminals to a court-martial for sexual assault or any crime. Removing commanders from that process would weaken the military and result in fewer suspected sexual assaults being prosecuted, not more.”

The Military Needs a Proactive, Not Reactive Approach to Deal with Sexual Violence

A multi-pronged attack is needed to address the continuing sexual violence epidemic. The military and Congress need a fundamental shift from a reactive approach to sexual violence to a proactive footing more in line with the military’s noble ideals.

I was 22. I never reported it for fear of backlash. Why would I, when the most they did for another girl who reported a different person was ask her if she led him on?#IAMVANESSAGUILLEN pic.twitter.com/EbyOo8R7me

— Karina @ KEEP FIGHTING (@BigTofuu) July 1, 2020

Four years ago, Congress passed the Military Justice Act of 2016, which then-President Barack Obama subsequently signed. Senator John McCain (R-AZ) noted that the Act “constituted the most significant reforms to the Uniform Code of Military Justice since it was enacted.”

The law provides robust protections for victims and borrows from best practices in the civilian criminal justice system.

The military should also expand its sexual violence refresher training for all servicemembers and actively punish those who retaliate against a victim.

Commanders could also consider the situational risks of sexual assault, and provide informed safety briefings during high-risk periods, such as holidays and deployments.

Finally, the Department of Defense could implement service-wide prevention and intervention measures that would encourage victims to come forward.

The military #MeToo movement is long overdue. Military sexual violence is incompatible with the warrior ethos that soldiers, sailors, airmen and marines live by every day.

A proactive approach to tackling this important topic can only help, not hurt, unit cohesion and good order and discipline in the ranks. People need to feel safe to perform their jobs most effectively.

The continued lethality of the U.S. military and our ability to defend the country that we love tomorrow may depend on how well we handle military sexual violence today.

Comments are closed.