Editor’s Note: This article is the second in a series about the recruitment of women into human trafficking networks. Read the first installment.

By Larson Binzer

In 2010, at a women’s correctional facility in central Florida, an unassuming correctional officer happened to attend a seminar conducted by the International Association of Human Trafficking Investigators. This voluntary training would be the first instruction on sex trafficking that he ever received. For the next six years, John Meekins would go on to dedicate much of his time to studying the jailhouse recruitment of women into human trafficking rings.

After that first training seminar, Meekins thought back to earlier parts of his career and the obvious signs of trafficking and abuse he had missed. This prompted him to begin a “low key” anti-trafficking campaign in his prison by putting up posters that defined human trafficking and provided information about how to report it to prison authorities. The administration has allowed his self-styled campaign, but has not officially endorsed it.

[Related: The Prison Pipeline: Recruiting Women into Human Trafficking Networks]

Several weeks after he began his efforts, an inmate approached Meekins and told him that she had been charged with prostitution, but had been under the control of a trafficker named Black who was now demanding that she use her time in prison to recruit other inmates into their circle. She showed him the first of what would turn out to be dozens of letters, in which he wrote:

“We need a team of like 8 solid bitches who not on no jealous shit and we cannot go wrong,” Black wrote. “Baby I know there are hoes in there with you and I know you know real people so make it happen.”

[Related: Know the Language of Human Trafficking: A Glossary of Sex Trafficking Terms]

It was the first of many similar instances Meekins has since encountered. Trafficked women often bounce in and out of correctional facilities on prostitution arrests. While in jail, these women can be used as liaisons for human traffickers to handle in-house recruitment. When the fresh recruit is released, her transition into the trafficking ring will already have been facilitated by mail.

[Related: Combating Human Trafficking Network within Prison Walls]

Among Black’s letters to inmates, Meekins found several that provided a window into the methodology of human traffickers. Black would ask his targets intimate questions: What were their hopes and dreams when they got out? What did they want? What drugs did they like? Subsequent letters would be filled with promises to fulfil these dreams. They also confirmed the specifics of who would collect them once they were released and what life would be like.

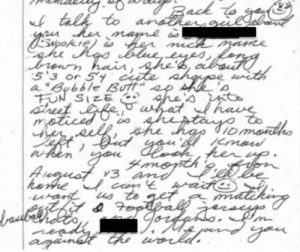

Below is an excerpt of this type of letter from a pimp to an inmate. It’s from a recruiter reporting on her enlistment efforts inside:

I talk to another girl about you, her name is [withheld] (Snookie) is her nick name she has blue eyes, long brown hair, she’s about 5’3 or 5’4 cute shape with a “Bubble Butt” so she’s FUN SIZE (insert smiley) she’s into street life, what I have noticed is she stays to her self, she has 10 months left, but you’ll know when you look her up. 4 months from August 13 and I’ll be home I can’t wait (insert smiley) I want us to get a matching outfit & football jerseys baseball hats, and Jordans. I’m ready [name withheld.] Me and you against the world.

Meekins explained that a letter such as this one would then prompt the pimp to reach out to the target and entice her into his ring.

“Heard soooo much about you from my lady,” one trafficker’s letter to a prospect reads. It is dated November 6, 2012. “I feel as tho I already know you. For sure everything I have heard has been positive. You are more than welcome to join our force. As my lady stated we will come pick you up.” He tells her he has seen her photo on the website of the Department of Corrections (DOC) website. “Think you are a pretty young lady.”

Jan Miley is a trafficking survivor who spent 11 years under the control of eight different pimps, resulting in more than 20 arrests for prostitution, grand theft auto, and drug possession. The psychological and physical abuse she experienced was extreme. Like many girls in her pimp’s stable, Miley knew that even though she was not a recruiter, girls in her ring would receive better treatment like new clothes, hygienic products, or fewer beatings if they recruited new women into her trafficker’s group.

“It makes them happy when you bring new girls around,” she told me. “That’s more money in their pocket and then you benefit from it as well, maybe for a short time and you only have it one time. But for that little bit of time, you could benefit from it and then they look at you like you did something good. It makes you feel good.”

Tena Dellaca-Hedrick, another trafficking survivor, has also been a victim advocate at a sexual assault treatment center in Indiana since 2009. She said that during exchanges between a pimp and his new recruit, the women being trafficked will already begin to feel indebted to their prospective new boss. From the beginning of this correspondence, the trafficker will start putting money into the woman’s commissary account —say $10 a month— as a loan.

“What they don’t realize is that $10 comes at extremely high interest rate, so when you get out of prison you might have borrowed $100, or you might have borrowed $500, that $100 is now $10,000 or that $500 might be now $50,000 due to the interest rate piped on the borrowing,” Dellaca-Hedrick said. “So it is kind of shocking, and in the end they find out they cannot work a regular job and pay that back, and the pimp says ‘I got a job for you to pay that back.’ So they are indebted, then, to that human trafficker.”

The traffickers often compound the indebtedness with romance. Through this psychological manipulation, and because the woman comes to believe they are in love, a pimp can make his new prey more accepting of his brutality or the strict rules he imposes. The most important part to understand about these victims, Dellaca-Hedrick said, is that the pattern of psychological torment is particularly acute for those who are “gullible” and “looking for love.”

A search of the DOC website, where mug shots and individual stats are publicly available, is a marketing bonanza for human traffickers. They can easily target victims of the ethnic or age-group demographic that appeals to their clientele. A categorical search of the site will turn up women by mug shot, crime, release date, physical coloring, height, weight, ethnicity, and age.

“It’s like picking women off a menu,” said Jose Ramirez, a special agent for the Metropolitan Bureau of Investigations, a Florida task force founded in 1978. Ramirez is in charge of the unit that works on trafficking cases in central Florida. He told me that the DOC site makes it easy for human traffickers to select the youngest and most attractive girls in the system. Since the problem of trafficking has become more evident over the last decade, the bureau now works with FBI, local agencies, and law enforcement to track and capture human traffickers in the area.

“In my specific case, the man had a girl within the system who was working as a liaison for him, to recruit girls,” Ramirez said. They also found, and subsequent cases have also shown, that the debt inmates accumulate from money being added to their commissary accounts, through JPay, is a way for human traffickers to entrap women upon their release.

In an effort to combat prison recruitment, Ramirez has joined forces with the American Correctional Association to provide more targeted training for staff. He supports a decrease in public access to the personal information about individual inmates.

However, he also realizes that more is needed beyond addressing these obvious structural flaws such as psychological screenings for incoming inmates and specific training for medical personnel to identify signs of trafficked women. That is also apparent to Tomas Lares, who co-founded and chairs the Greater Orlando Human Trafficking Task Force. As a collective group, Lares said, the prevalence of abuse and instability in the personal histories of many inmates makes them particularly vulnerable to human traffickers who will give them what they want and need.

“Unfortunately, it’s such a breeding ground and such a perfect storm for recruitment because the women are either addicted to a substance, have been arrested multiple times on different charges, or have a history of abuse,” Lares said. “We see the majority of our clients were abused as a child where there is some form of a neglect or physical abuse. Their vulnerability is at its highest. They’re hitting rock bottom.”

Lares cited Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs to support his observations. Because many women newly out of jail don’t have easy access to food, shelter or clothing, human traffickers can entice them with relative luxuries like “drugs, Wendy’s meals and shopping sprees,” said Lares. Then they can convince them that sex work will be an expedited means of repayment instead of the actual extortion it is.

The Anti-Trafficking Task Force —”Florida Abolitionists”— is in the earliest phase of creating a program with the University of Central Florida. Their mission is not only to address the systemic problems, but to also educate female jail populations about how to recognize if they are victims of manipulation or sexual exploitation. Until the program is under way, the task force has been concentrating on training police officers, correctional staff and other professionals who come into regular contact with inmates on how to identify victims.

Among these groups are chaplains who, especially in central Florida, are often very involved with inmates and have proven to be excellent at identifying trafficking victims. Since the task force’s first training session for this group back in 2012, the number of reports of both potential victims and recruitment has increased significantly.

However, despite all the independent efforts trafficking is receiving in the region, the Florida Department of Corrections has not increased its efforts to investigate the reports that have been filed. Ramirez emphasized that without appropriate training for correctional personnel, officials will not even be able to recognize signs of trafficking to report to the bureau.

“It’s not easy to identify someone who might be involved in trafficking in the jails,” Ramirez said. “We have been working on how to develop some kind of training. A lot of stuff is being done across the nation, so I want to find out what kind of tools we’re going to use, and what kind of training to utilize to train all correctional people.”

Comments are closed.